Interviews

Tay Zonday Opens Up About 'Chocolate Rain' Going Viral And The Struggles Of Internet Fame As We Look Back On The Last 14 Years

he experience of “going viral” and becoming a meme is something that few people will ever encounter. While some of these instances are mostly positive for the person depicted in the meme, other times it can be a whirlwind of events and unwanted exposure online — completely out of one’s control. This is especially true for those who experienced this rare phenomenon during the earliest days of internet culture and online virality, such as Tay Zonday, whose real name is Adam Bahner.

Just about everyone today has heard of or listened to “Chocolate Rain” at one point or another during its last 14 years online, and while some of these viewers think they know the man behind it, they probably have no clue. We recently sat down with Bahner to discuss the creation of his viral hit "Chocolate Rain," who opened up about his struggles with mental health and being true to himself and his artistic vision as he reflects on the experience all these years later.

Q: Hey, Tay. Thanks for joining us. Let’s start off with a quick intro about who you are and what you’re known for online.

A: I’m Tay Zonday. My public online recognition began with “Chocolate Rain,” a song I uploaded to YouTube that went viral in July of 2007.

Q: Could you tell us a little more about your background before we get into “Chocolate Rain” and the mid-2000s? How’d you first get into making music and singing?

A: Music was never my “main” life path. I began to play my family’s baby grand piano as a hobby around age 3. I dabbled with formal lessons from ages 5 through 10 but they just didn’t work for me. In hindsight, a lot of things that worked (and did not work) for me as a child may relate to autism spectrum disorder, something I was first diagnosed with at age 15. I continued to be a hobbyist musician into adulthood.

Q: What about your stage name “Tay Zonday?” Where’d you come up with this pseudonym originally and why’d you want to distinguish it from your real name?

A: Adam Bahner is my birth name. In 2007, I was three years into graduate coursework for my Ph.D. in American Studies. American Studies is basically history with extra flavors you choose. I believed that my professional future would consist of publishing academic research and teaching as “Adam Bahner.”

Meanwhile, my lifelong music hobby continued. I would attend open-mic events around the Twin Cities. I admired the countless pipe welders, beauticians and people with other “day jobs” who created beautiful musicals for the Minnesota Fringe Festival and other local events.

YouTube started to grow as a platform, and I saw an opportunity to reach more people — with less hassle than dragging my 40-pound keyboard and 30-pound amplifier across town during the bitter winter. I wanted to create a memorable name that would never conflict with my academic work. I typed “Tay Zonday” in Google and it got zero results.

Q: When did you start your YouTube channel and begin some of your earliest forays into content creation?

A: I created my “Tay Zonday” YouTube channel in January of 2007. It was simply a venue to share experimental music and receive feedback.

Q: So you uploaded “Chocolate Rain” to your channel in April 2007, but can you give us the full backstory of how that song came to be? How’d you come up with the lyrics, and what was it really about for those who are unaware?

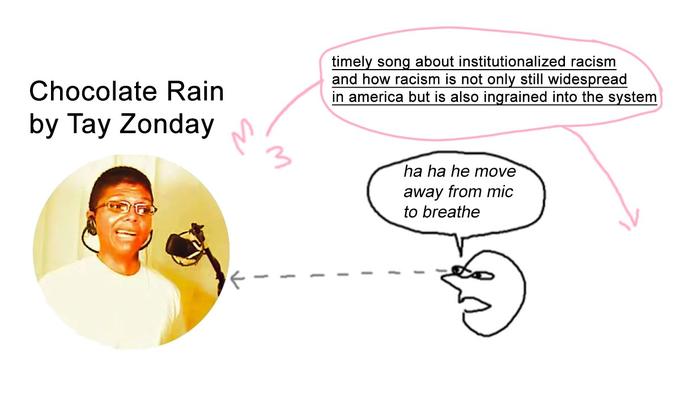

A: Stephen King states in his book On Writing that no author truly knows where their art comes from. You get to a place where it just happens. The riff for “Chocolate Rain” had been in my mind for many years. I wrote lyrics to it over a period of roughly six weeks. I was volunteering a lot at In The Heart Of The Beast Puppet and Mask Theater at the time. In some ways, “Chocolate Rain” is a physical metaphor for the song’s staccato counterpoint and my fingers on the keys. But I also wrote the song as a ballad about institutional racism. Is that really its meaning?

I’m not an enforcer. I don’t like to police how individuals experience my art. When a song goes viral, it’s like your artistic child is adopted and raised by the public. It’s not my kid anymore. Did people find many different ways and meanings for the song to make them happy? Yes. But that’s the case with all music. Music is a trojan horse, not a battering ram. It gets inside you under a million pretenses. It’s not polemic, it’s corrupting. Just like history and economic power.

Q: Upon posting it to YouTube, what were your initial expectations for it? Did you think it would be a hit or were you surprised by how rapidly it went viral and became a sensation?

A: I rushed “Chocolate Rain” to completion because another song of mine, “Love,” was picked by YouTube to be a front-page feature. I wanted to double-dip on the exposure and have a new song on my YouTube channel while the old one got featured. Nothing about it stuck out to me at the time besides being another piece of experimental art.

When it went viral, internet virality wasn’t a widely understood experience. I was an unwitting national news story. I didn’t have a lot of “real-world” social or business experience. It felt, in the first weeks, like 15 minutes of fame. I didn’t know where it would go. I also didn’t, fundamentally, empathize with its popularity. I appreciated it. But what I now realize is that in my own journey with autism spectrum disorder, I can’t relate to a lot of human experiences. When I say “Chocolate Rain’s” virality puzzled me, my baseline is that most things profoundly puzzle me. I’m always a wet fish in an ocean of confusion. Maybe songs make sense of it.

Q: After it had gone viral, tons of shows from G4TV’s Attack of the Show to Tosh.0 and Jimmy Kimmel Live began having you make appearances. What was that whirlwind of press and coverage like back then? Was it a fun experience or was it more stressful?

A: I needed more time to prepare for the inundation of record labels, television producers, booking agents, venues, parents throwing bar mitzvahs and everybody else who tried to contact me during the summer of 2007. But it was happening right now. Correspondence was in triage mode. My brother started to help manage me, but it was still overwhelming.

Most of my live appearances were awkward, uncertain escapades in which I felt like a kayak being carried forward by a fast-flowing current with thousands of voices lining the shore saying “Do something! The river’s about to end!” I said “yes” to a lot because I honestly didn’t know how else to learn about opportunities.

Q: You also did many, many commercials, appearances in music videos and songs, such as the NASA presentation, Vizio’s Super Bowl commercial, etc. What were some of these experiences like for you, and was there a favorite one that you got to work on?

A: Let me make one thing clear: I’m grateful for work opportunities and to anybody who hires me. That being said, many of the things I did which involved actual human contact in real life, like Jimmy Kimmel or singing at First Avenue or appearing on MTV’s Best Year Ever … I feel like I was stiff, apprehensive and awkward in person. I was not the guy from the “Chocolate Rain” video, even when my job was literally to play him. The YouTube version of me was better.

Autistic people have a term called “masking” to describe trying to imitate a person who is not autistic so they can blend in with society. In hindsight, singing in my living room in front of a bedsheet on YouTube was, at the time I sang “Chocolate Rain,” an environment that accommodated my sensory needs without as much pressure to engage in masking.

The spotlight of public attention threw me into a lot of environments and situations where everyone else celebrated the “Chocolate Rain” guy. But inside my brain, he was just one of many norms to comply with in an effort to simply exist around humans, something that always required exhausting mental effort because I’m autistic.

I was first diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at age 15. However, I didn’t know enough about my diagnosis or what it meant about how I had to live my life until a lot of failures prompted serious self-reflection in my late 30s, more than a decade after “Chocolate Rain” went viral.

Q: What did your friends or family think of your viral internet fame back in the day? Can you tell us how some of them reacted to this early on?

A: How do most healthy friends or family react to a person’s success? I don’t recall any outlier experiences. They were happy for me. Encouragement and praise are nice, but I’ve never known what to do with praise or accolades. Compliments don’t necessarily track with business or artistic success. I’ve also never been rich from “Chocolate Rain.” I’m grateful, but I wasn’t suddenly paying off mortgages for Christmas. I was never that son or sibling.

Q: In the following months and years, numerous memes, remixes or parodies using your song began spreading all around the web. Did you enjoy seeing people reference “Chocolate Rain” in this manner, and do you have any favorite examples or specific types that you find the funniest or best?

A: I rarely keep track of how people appropriate me. Maybe it’s just not operational in my day-to-day life. If somebody finds happiness, good for them. It’s interesting to be parodied on stuff like South Park and Saturday Night Live. But if I had to choose between being parodied by famous franchises and taking a boring, secure life path at age 22, like a career at the Social Security Administration, I’d tell the younger me to take the other path. I’d have a lot more clarity about my future today.

Q: Several music icons, such as Kid Cudi, have noted they’re fans of your work over the years, so what’s it like seeing some of those huge industry giants shouting out your music online?

A: I appreciate it. That’s very kind when anybody shares a positive experience with my art. But then again, people are people to me. When you meet celebrities, they’re just a slice of humanity.

We get way too caught up on the mythology of meritocratic individualism. Don’t we lionize celebrities because they made something that we experience to be beautiful? Don’t we romance their apparent defeat of financial scarcity? What if we didn’t normalize our species as emerging from a scarcity of beauty or providence? What if we found that baseline to be anomalous?

Love my fans @KidCudi pic.twitter.com/wZMsEU2hFQ

— Tay Zonday (@TayZonday) May 2, 2020

Q: Your song “Internet Dream” feels particularly relevant today despite being over 13 years old now. Can you tell us how you came up with this song and what your thoughts are on how it applies to the modern landscape of the internet?

A: The internet stopped being a discrete phenomenon with the rise of smartphones and recommendation engines. We are penetrated. Dreams are inherently internet dreams. Plus, the internet is a machine-learning artificial intelligence that in its own gated, private-sector and unaccountable way … now dreams about us. The more balkanized, gaslit and keyword-metadata-compliant we are, the more we make the internet’s dreams about us come true.

Q: Before we move on to some of the other songs and more recent work, how do you feel about how YouTube and the nature of viral videos, in general, have changed over the years? Do you think it’s better, worse or somewhere in-between these days?

A: YouTube has switched from a novelty economy to a loyalty economy. Before YouTube spied on user behavior to show each person what keeps them most addicted to the platform, the content that got popular was grounded in novelty. Humans shared videos that were new or unusual experiences.

Now that YouTube is a machine that cherry-picks videos to show you whatever keeps you watching ads the longest, the gatekeeper of video views is audience loyalty. This is great for business and bad for humanity.

Sometimes humanity needs to be alienated. Civil society needs people to see content that upsets them. Civil society needs to have its conscience shocked. The comfortable must be afflicted.

George Floyd’s horrific murder was upsetting and traumatic. It didn’t go viral on YouTube. It went viral on other platforms. On YouTube, it got creators like Philip DeFranco who tried to talk about it punished. His viewership would be nerfed. The machine would not send the topic to his audience.

Advertiser anxiety also dictates who is allowed to talk about upsetting truths on YouTube. CNN is allowed to — Phil DeFranco isn’t. The human beings at YouTube deny this. They’ll say, “That’s not our policy.” But when their machine-learning artificial intelligence picks winners and losers with zero transparency, we can’t take the machine to the International Criminal Court and prosecute it for cutting moral corners. The machine won’t give a deposition.

Q: So all these years later, you still create content on your YouTube channel occasionally despite having a rich career offline doing music, voice acting, etc. Can you tell us why you still do YouTube content and how that differs from your other work?

A: The function of my YouTube channel hasn’t changed since 2007. If I have creative work to share, I share it. Most of the time, I live with debilitating anxiety exacerbated by unending recognizability and autism spectrum disorder — with no financial means to access a sensory environment that would facilitate my creative peak performance. But intractability is the norm of human experience. There is nothing differentiating about the current of adversity being faster than you can row. That’s the plot of every memoir that doesn’t get written.

Q: Voice acting seems like a particularly interesting part of your career post “Chocolate Rain,” so what are some highlights from over the years in this area that you’ve enjoyed the most?

A: I am very lucky when anybody believes I’m the right talent for their project. I’m grateful. I take nothing for granted. But I’m also reluctant to name-drop recognizable work. I’ve just never been that person at the party. When I’m blessed that a client appreciates my work on its merit, their project is where the spotlight belongs.

I’ll make one exception: My friend Rich Arenas is a brilliant arranger who used my vocals on some tracks for Adult Swim’s Gemusetto Machu Picchu in collaboration with Maxime Simonet.

Q: You frequently post fan tributes and things from your followers to your social media. How do fan interactions typically go and what are some of your favorite fan arts, renditions of your songs, etc. that you’ve received over the years?

A: I don’t know how to answer this. Is it this deep? If anybody derives positive energy from my momentary flash between the cosmic cradle and cosmic grave, good for them. I appreciate them.

You’re asking me to intuit individuals. I intuit systems. I intuit strictures. I feel complex systems as though they are human beings. They are the characters I relate to most naturally in life. Feeling and speaking for the forest is my superpower. That comes with a high price: I feel blind to the trees.

Q: Since you hail from the days of early internet culture, what do you make of the current memescape these days? Do you have a current or all-time favorite meme?

A: I’m terrible at following the current memescape. I’m still a TikTok novice. I come from a world where memes had more time to convey a message. There aren’t any more five-minute memes.

One thing I will say: The dividends of the enlightenment in the form of literature are locked up in books and academic journals that kids can’t afford. Memes on free social platforms can’t fill this education void.

When you are frustrated by the state of the world, keep this in mind: The guilty are not on TikTok. The guilty are not on Twitter. They aren’t memes. They aren’t shading, dunking, dragging, ratio-ing or whatever verbs the cool Zoomers invent.

The guilty built complex systems of distraction and oppression. They built complex policies that you experience as normal. They aren’t public figures outside of their vocations. The spectacle of social media drama isn’t where they enact — it’s only where they coerce.

To borrow Ralph Ellison’s metaphor, I think memes are the shadow. Power is the act. The act is longer than 15 seconds or 280 characters. To change the act, we have to operate with the complexity, strategy and intention of those who created the problem.

Q: Alright, so in closing here since we just passed the 14-year mark since “Chocolate Rain” was first posted, how do you look back and reflect on the whole experience of “going viral” and becoming an internet star all these years later?

A: From a mental health standpoint? Perhaps I’d have been happier living a creative life like Emily Dickinson. Posthumous exposure is easier to handle. Tay Zonday was probably better left a mystery. Disembodied. Context-free. Unacknowledged. I talked too much and did too much as Adam Bahner but called it “Tay Zonday.” I’d attend parties in Los Angeles where half the people knew me as “Tay,” the other half knew me as “Adam,” and I only knew myself as confused.

Clark Kent ruins every Superman plot if he can’t make Superman happen but runs into burning buildings anyway. I was too autistic to make Tay Zonday happen beyond the comfort of anonymity in my living room. But I kept trying. And failing. I will never have that anonymity again. Maybe doing an interview like this worsens the problem, but I’ve been creatively silent in a strange selective mutism triggered by a perpetual lack of privacy and not sure how to be well. I should testify to that paralysis while I still can.

From a financial standpoint, there were much better life choices I could have made to reduce the odds of a future in homelessness or destitution. I should probably have become a radiologist, but lots of people say “woulda coulda shoulda” as their life progresses.

Q: Any final word, closing statement or additional info to add?

A: Today, I feel absolutely terrible plugging myself. Sometimes I work myself up to do it. But it’s hard for me to find that mood now.

Why do any of us deserve to live in a world of scarcity where we must endlessly go “tell ourselves on the mountain” and evangelize our individual worth to vie for a lottery ticket to have our human needs met?

Our needs are a fraction of our species surplus and poverty is a policy choice. Scarcity is a voluntary structural design to compel involuntary participation in systems that don’t benefit the majority. I was not built for these contrived hunger games. Were you?

Watch our interview with Tay Zonday for the video version of our discussion below.

Tay Zonday is a singer, songwriter, voice actor and YouTuber known for his viral video “Chocolate Rain,” which became the subject of memes and fan art throughout the late 2000s and 2010s. To keep up with Tay, you can follow him on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter or check out his YouTube channel for more.

Comments ( 2 )

Sorry, but you must activate your account to post a comment.