Probably it would be a good idea to look up the Roland Barthes essay where he coined the term, which you can find here.

It's a rather complex essay, but to the extent that it can be boiled down I'd reduce it to two main points:

1) The author's intentions are unknowable.

2) The demand that criticism always refer to authorial intent is a pointless constraint.

As for point 1, it strikes me as a rather simple issue. You cannot read minds, first of all, and even when an author reports on their goals, they may not be entirely honest, or may simply not remember what they thought at a given point in time. It's entirely possible, for instance, for an author to write a story, then later notice a pattern or theme that emerged by chance, and then say, when asked, that it was their goal all along – either because they mis-remembered, or because they lied.

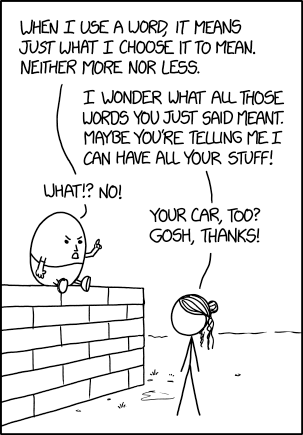

But point 2 is both more interesting and more important. As Barthes writes, "The reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost; a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination." Which is to say that the meaning of the text does not emerge from the writing, but rather from the reading. The reader, often understood as a passive recipient of information, is actually an active, powerful figure, the one from whom meaning arises. It is for this reason that Barthes refers to the "author" as a "scriptor" throughout the essay – to imply that they serve a largely secretarial function, more like a photocopier than a genius.

As for the remake of the Lord of the Flies, if we buy Barthes's argument it follows that neither Golding's opinions on the role of gender in his story nor the opinions of the people doing the re-make should hold any special importance. One should treat them as one would any literary critic: you should put their words next to any other paper on the role of gender in LotF and let them compete on their merits alone.

Far more important here is the larger reaction to the film, both to the idea of it (which is all we have at the moment) and later to the film itself. Gender representation is a dynamic system that responds to everything that touches it, so it makes no sense to treat the response to the story as separate from the story itself. What we must remember is that, while the writers and directors of the film are responsible for arranging the images presented in the film, they have no special role in determining its meaning. We, the viewers, perform that role: that is the source of our power.